Proving Determinism (A Thought Experiment)

“God grant me the serenity to accept things I cannot change,

Courage to change things I can,

And wisdom to know the difference.”

— Reinhold Niebuhr

Everyone at least acts as though they have the power to make their own decisions. Yet, when we reflect upon what we know about the natural world, it seems like this shouldn’t be impossible. Instead, the thoughts you have should be cold, neurochemical reactions you have no control over. Similarly, chance must also be an illusion. If you win the lottery, the luck you perceive wasn’t really luck at all: turning the clock back would yield the same result over and over again.

Serious belief in the idea that “all things happen for a reason” is referred to in philosophical circles as Determinism. Determinism appears to be a natural consequence of the laws of nature and what we’re taught in physics. In this post, I’ll argue that from within a deterministic world — even one with trivial laws governing it — there’s no way to know if the world is truly deterministic. Along the way, I’ll also do a brief dive into why I don’t find the state of physics sufficient for figuring out if the world is deterministic, set criterion for what a good answer looks like, and teach you a fair amount about Conways Game of Life, a famous computer program.

“The world is governed by (or is under the sway of) determinism if and only if, given a specified way things are at a time t, the way things go thereafter is fixed as a matter of_natural law.” — Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Where Physics Falls Short

Many people are allergic to philosophical speculation based on physics. Here, I explain why. You can skip this section if you really want, but you shouldn’t. The arguments in this area are fascinating, even if they’re incomplete. This section isn’t necessary to understand the argument. Instead, it is the motivation for the approach I take later.

Physics is a natural first place to look for answers about the world we live in because it is the most precise set of theories we have. Physics, in short, aims to understand how the universe behaves. The precision to which we can predict phenomena in our world using physics is perhaps the most fruitful ground for deterministic thought today. Predictability is married to determinism. A perfectly predictable world would leave us with a strict march of events, one after the other; there would be no room for free will or chance. There are two major constitutions that are at conflict for the laws physics as we know it: quantum mechanics, and general relativity. Each has phenomena they explain well. Relativity describes the motions of large objects — think planets and galaxies — while quantum mechanics describes small ones, like particles of light. The two are in disagreement with one another, so we should tackle each independently. Let’s examine general relativity (GR) first. Outside of entirely philosophical arguments, GR lends itself to determinism in all but a few edge cases. Additionally, Einstein, GR’s founder, was an outspoken determinist [1]. However, in the direct results of Einstein’s own equations, determinism can fail to hold. For example, in some models of black holes, determinism breaks down and the future can no longer be predicted using physics.

Any breakdown of causality should be impossible for someone with a deterministic worldview. There’s a conjecture called the Cosmic Censorship hypothesis arguing that while a breakdown of causality is theoretically possible under GR, the circumstances under which causality breaks down must not be present in our universe [2]. However, Cosmic Censorship is just a conjecture, there’s no proof for or against it. This leaves determinism under GR in a gray area, philosophically speaking.

Artist’s illustration from a Quanta article on cosmic censorship. Notice how the singularity spreads out and could potentially be observed by an outsider.

Unlike Einstein’s theory of relativity, the implications of quantum mechanics are famously up to the interpreter. The most popular framework for understanding quantum mechanics is the Copenhagen Interpretation. In it, phenomena like radioactive decay are thought to have truly probabilistic components to them [3]. Under this reading, there would truly be events thathave no explanation[4]_._The bizarre philosophical state of quantum mechanics has opened up the door for people of every metaphysical predilection to use it in their defense, rendering it unhelpful in the debate for determinism. If you’re a determinist, the chancy-nature of quantum mechanics is simply a weakness in the theory. Others who believe in free will argue that the randomness in quantum mechanics scales up to the neurological level, resulting in the probabilistic firing of synaptic vessels providing a basis for free will. Like general relativity, quantum mechanics provides no clear path to determinism. Neither of the most advanced theories in modern physics has an answer to the determinism debate. Let’s take a step back and look at the nature of the debate itself.

The Ideal Explanation

Strictly speaking, I see four ways to come to a conclusion about the question of whether the world is deterministic_._The first two go about it by proving determinism. The second two proceed by showing_indeterminism._Indeterminism, not to be confused with free will, is the idea that an event can occur without cause (interesting endnote on this at [5]). Here are the ways we can arrive at a conclusion:

- Devise a convincing Theory of Everything. If the Theory of everything lacks probabilistic components, the universe would be deterministic.

- Show that a world where events can occur without cause leads to some contradiction.

- Find at least one event that — provably — has no cause. Many physicists purport that quantum mechanics has shown this to be the case, but many still believe there must be something missing [3].

- Show that in a deterministic world there is a contradiction; this might manifest itself by showing that there’s something that exists in the real world that could not possibly exist in a deterministic one or vice versa.

I’m going to spend the rest of this post exploring options 1 and 4 by simulating a deterministic world and paying attention to two separate issues:

- From within a deterministic world, do we see anything that is incompatible with our own? This would violate question 4 above.

- From within a deterministic world, could we ever find a Theory of Everything? This would make 1 unprovable.

Let’s talk about how we will simulate a deterministic world.

Imagining a Completely Deterministic World

A simulation of the real world is out far beyond the computing power we have today. Instead of imagining something so ambitious, I’ll use a popular “simulated world” called Conway’s Game of Life (GoL for short) as an analogy and make the case that answers that hold for GoL would also hold for our world if it were deterministic. In particular, we’ll be interested in whether creatures_inside GoL_would be able to confirm or deny that their world was deterministic, and we’ll extrapolate on that to imagine if we might be able to as well.

This is a textbook case of analogical reasoning. I have a whole post on what makes a good or bad analogy. Check that out if you see this as a bad analogy and want to come at me with my own logic.

GoL is a cellular automata, a simple computer program that has a short set of rules and fascinating, life-like, output. There’s no randomness inserted into in GoL, so we can safely say that it is deterministic in the sense that we care about. It’s worth considering whether a deterministic world could produce something similar to the one we see on a day to day basis. It’s not at all obvious that simple, deterministic laws could produce the world we live in; for a long time this was even considered a competitive argument for all-powerful creator. GoL has silenced any fears I’ve had about a deterministic world being unable to produce the complexity we see in the actual one.

Example output from Conway’s Game of Life (source)

I’ve also talked about cellular automata in the past, so if you want an in-depth explanation of how cellular automata work — including GoL — that post is the place to go. I’ve also written a library to generate them.

You won’t need to know too much about how GoL is constructed for this post. You’ll just need to know why it’s a good analogy for imagining a deterministic world. Below I give a couple of similarities between how we imagine a “real” deterministic world and GoL. `

Similarity #1: There’s a small set of laws that all other rules are derived from.

The guiding principle of a deterministic worldview is that there are some laws of physics that all other behavior is derived from. By definition, this is what is happening in GoL. In GoL, each “cell” (row and column in the grid) is computed according to 4 simple rules. I won’t write them out here, but if you’re interested, read my other blog post on the topic.

Similarity #2: There’s life-like output.

In any candidate for a deterministic world, we would expect to see “organisms” that behave something like the way organisms in the real world do. Let’s see an example:

A zoomed-in collision between two “organisms”. The large structure is known as a “pulsar” and the moving structure is called a “glider”. The above image was generated with the library I wrote. These are some of the simplest organisms that can arise in GoL.

GoL is special because some the organisms satisfy John von Neuman’s two criteria for a living being:

- Reproduction: In GoL there are creatures that can copy themselves, much like living cells in the real world. The first self-replicating creature

- The ability to simulate a Turing machine: In GoL, provided you can find the right configuration of creatures, you can run any arbitrary program. For example, you could build Tertis on GoL, or Skyrim, provided you don’t care how slow it runs. GoL is what’s known as a universal Turing machine; you can run any program you can imagine on it.

#2 is likely unfamiliar for readers without computer science backgrounds. It means that, in principle, there’s nothing stopping GoL from producing “intelligent” creatures. It’s not difficult to imagine that on a large enough grid, given the correct initial input, that GoL would produce something akin to a creature piloted by a machine learning algorithm optimizing for it to “survive” and “reproduce”. Genetic algorithms and artificial intelligence are not out of scope either, as GoL can compute anything that is computable.

This is an example of someone building logic gates using GoL creatures. In computers today, we build logic gates out of transistors, then from those logic gates more complex circuits — like the arithmetic units of CPUs — and ultimately whole computers. There’s nothing preventing this sort of thing from happening in GoL.

Similarity #3: There’s no randomness, but we see pseudorandom behavior anyway.

The primary complaint with the concept of a deterministic world is the presence of events that appear to be probabilistic (quantum mechanics, financial markets, etc). Any strict determinist will retort that — despite the best efforts of physicists — the events only appear to have random components. An imaginary deterministic universe must contain events that seem random but are really the product of deterministic laws. We can show that GoL has this because it has been proven to beundecidable.In other words, given some initial state and some later state, there is no algorithm to show with certainty whether or not the later state will appear. Remember, this doesn’t break the fact that GoL is deterministic, it only means that the whole system needs to be computed_step by step_to arrive at an answer. What undecidability means for this argument is that even if some algorithm existed to predict arbitrary states of GoL statistically, it would never reach perfect predictions. Far-out predictions in GoL are probabilistic, much like our world.

In particular, we’ll be interested in whether creatures inside Conway’s Game of Life would be able to confirm or deny that their world was deterministic, and we’ll extrapolate on that to imagine if we might be able to as well.

Thought Experiment: Showing GoL is deterministic from within GoL

Provided the above justification is enough to show that a deterministic world is at least feasible, we should ask whether a theory of everything could ever actually be proven in that world. If our deterministic world is GoL, then we need to see if we can imagine an experiment that would prove determinism within GoL. To do so, we’ll take as many liberties in the potential configurations of GoL as its rules allow. But first, let’s go back to our guiding question:

From within a deterministic world, could we ever prove determinism?

Given that we’ve chosen GoL as our deterministic world and the ability to provide perfect predictions of arbitrary events as our method of showing determinism, we can reformulate the question.

*From within any GoL world, could there be a structure that could yield perfect (and confirmable) predictions for the configuration it was in?

If the above statement is true, then by analogy we have evidence that the original statement might be true as well. The statement I have above might seem vacuously true at first, after all, we’ve already showed that GoL can simulate GoL. It’s actually not so obvious when you add the constraint that the GoL predictions need to be confirmable from within the same GoL configuration’s history. It’s easy for us to tell that GoL is able to simulate itself perfectly because we’re sitting outside GoL. For the above statement to be true, we need creatures within GoL to figure out that their world is predictable and non-chancy (AKA simulate-able).

Let’s try to imagine a structure where a GoL creature could figure this out. The structure has to be able to take in some state of the GoL that has occurred previously and output the next state of the GoL execution with perfect accuracy. It’s worth noting that predicting a couple of future state perfectly is probably sufficient, we don’t’ need to show that every state in history can be reproduced [6].

Nothing “close to correct, but not perfect” in terms of the input into the structure, or “close to correct, but not perfect” for the output should count as good enough for this predictor. This requirement might seem too strict at first, but it’s important.The reason we need perfect fidelity for our predictions is twofold. First, due to the chaotic nature of the GoL even a small error in our predictions will compound upon itself and cause the predictor to be radically incorrect very quickly. Chaotic systems are perfectly predictable, but only if their rules and initial conditions are known exactly. Second, without output and input that is exactly the next and previous state of the GoL, how could any agent within it be certain that the GoL was truly deterministic, and not just probabilistic? Let’s take a sketch of what this might look like in practice:

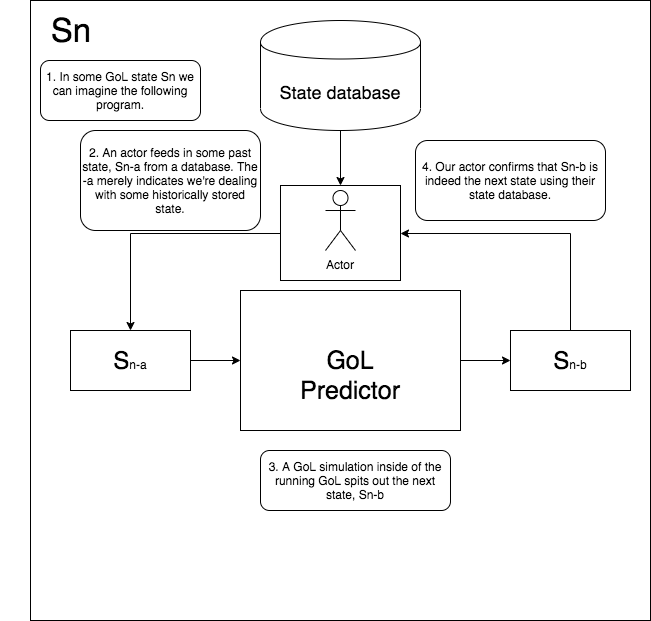

A diagram for a Game of Life state, Sn, that contains a GoL predictor, some past state Sn-a it wants to predict the next state of, and some state Sn-b that it outputs and confirms. Sn-a and Sn-b are pulled from a database of states that have occurred previously.

There are 3 major components in this thought experiment, excluding Sn, which is the “master” GoL itself. If all of them are feasible within the GoL, then we should be able to say that we could show that GoL was determinism from within GoL.

GoL Predictor

This one is the most feasible of the 3. All it has to do is to take in as input a state of the GoL and follow the rules to produce an output. This should be possible in principle as GoL is a universal Turing machine and can simulate any computer program (including itself, as shown a little further down!).

The OTCA metapixel — incredibly this simulates GoL within GoL!

I also don’t have any doubt that creatures from within GoL could discover the rules of GoL; the rules are incredibly simple and, as previously mentioned, there’s nothing stopping creatures with machine learning capabilities from existing within GoL. Conway himself has commented on this before:

“It’s probable, given a large enough Life space, initially in a random state, that after a long time, intelligent, self-reproducing animals will emerge and populate some parts of the space.” — John Conway (source)

There is one slight problem related to taking in related to taking in input the size of the program itself (Sn-a should be the same size as Sn) but this is could easily be alleviated by streaming the input in bit-by-bit; plenty of creatures in GoL can do this. Here’s an example:

A “Gosper glider gun”. Notice how this creature seems to “shoot” gliders out to the bottom left corner of the screen; mechanisms like that could be used to stream input into more sophisticated creatures like the predictor.

The Actor

This is a representation of whatever — or whoever — confirms or denies that the predicted state, Sn-b was really the state following the input state, Sn-a. All the actor has to do is compare the output of the predictor to the ground-truth stored in the state database to confirm that it is really the same.

Nothing about this is too challenging for a universal Turing machine unless you’re demanding the actor have an “interest” in what they’re confirming. As difficult as it might be to imagine, there’s nothing stopping a fully functional machine learning algorithm from running in GoL. Who’s to say that algorithm of sufficient complexity doesn’t have an “interest” in what it’s doing? Personally, I like to imagine that there’s “something it’s like” to be the actor, but this is not a strict requirement. I don’t see consciousness as a necessary condition for confirmation; the actor could be a philosophical zombie of sorts.

State Database

The state database needs to be able to store perfect fidelity copies of previous states of the GoL; this is the hardest of the three to imagine existing. There are two major issues here: storing a state, and capturing it.

Storage works

By definition, a lossless copy of any previous state of GoL has to take as much memory in a computer as a normal state; this poses a problem if we want to store one state within another. Storage isn’t a huge obstacle at first pass, after all, we have lossless compression formats like FLAC that seem to do just fine, but once we start thinking of the details of a compression algorithm things get trickier.

Compression technics leverage statistical patterns in the data they’re attempting to compress. Random data cannot be compressed. That being said, there are plenty of patterns to exploit in GoL, and there is well-known research showing that compression techniques exist for GoL. There’s no reason a compression algorithm for GoL couldn’t be replicated within a large enough GoL.

Another problem is that compression algorithms run*outside_the state of the program they compress. A compression algorithm is, at its core, just another program running on a computer; it is strange trying to imagine a program that can_compress itself_and then store that compression within its own memory space. Even if it sounds weird, I don’t think this should be impossible. Imagine, for example, two compressors each sitting in the corner of GoL’s map, each handling compression of the opposite side and storing it within the state database. Admittedly though, I’m not sure of an example of this that exists, as there’s no practical reason for a program to have its own compression algorithm in its memory.

Observation is too tricky

It seems like everything could feasibly work until you think of how the compressor needs to capture a single “slice of time” in GoL.

Fundamentally, to compress any information, that information needs read in some fashion. What a “read” means in the context of GoL, and in real life, is to move information from one place to another.

GoL has a “speed of light” of sorts, information within it can only travel so fast, one cell horizontally or vertically in particular. Capturing the state of any object requires sending a message to the object who’s state the compressor is capturing and getting a message back. By the time any message makes it to the object-to-be-read the state of the game has changed several times. To make matters worse, something could collide with whatever was capturing the information. It’s difficult to imagine capturing the exact state of GoL in any predictable fashion for this reason. Somehow, information from all over the game board needs to make it from individual cells to the compressor without being corrupted by collisions in future states.

You might think that if you relax the condition of needing a perfect observation of the state you could get away with a pretty good prediction, but this would only be the case if GoL wasn’t sensitive to initial conditions. Any small perturbations to the input state will cause radically incorrect predictions for GoL.

At face value this sounds like it might just be a technical detail and worth ignoring, but I think this might actually be a principal limitation. This detail isn’t just important because I can’t think of a workaround, but because it’s a limitation on systems in the real world. Gathering perfect information about an arbitrary particle in real life is limited by the famous Uncertainty Principle. We also, obviously, have a real speed of light that seems to limit the speed of information travel except for in some bizarre circumstances. It seems a perfect-prediction machine in GoL is unbuildable for some of the same reasons it might seem unbuildable in the real world.

Limits to Knowledge

Provided the above conclusions are correct, what does the world seem like for our actor? Even when they know all the rules governing their world, things likely seem random and chancy. There are still macro rules of thumb that the actor could figure out though; like when a glider and a pulsar collide, what happens could be known with some statistical accuracy, but there would always be a chance for black swans when something unexpected collides with the two. Overall, events would still seem probabilistic. Especially those in the far future. The actor might have confidence in some small set of cases, but there wouldn’t be much hope of*proving_if the world was merely chancy or deterministic. The actor could gain more and more confidence of the universality of the GoL rules by running highly isolated experiments, but perfect predictions of arbitrary events would always be out of reach; this would leave determinism in an unfalsifiable state, as error in predictions could always be chocked up to interference.

Falsifiability is important to me. I’ve talked before about a problem in philosophy of mind that seems intractable, and I’ve always had a hunch that many problems in metaphysics, like the one in this post, also lack the kind of verifiability that could make them answerable questions. Any statement that is unfalsifiable is — drumroll, please —_pseudoscience._For this reason, the epistemology of determinism is its most important facet to me. So far, it seems like determinism falls into the unfalsifiable category, even when you have the laws of your universe solved for.

A natural next question is whether free will is falsifiable from within GoL. Maybe the actor can’t distinguish between determinism and randomness, but they could at least dispel free will, no? Just like we were with determinism, we should be precise in what we’re talking about when we say “free will”. To me, a robust argument against free will would show that there are no instances where causation has begun with some agent [7]. This is an ambitious argument. To show it, you need to either prove that events cannot arise independently — this is effectively proving determinism as we’ve discussed here — or show that no “agent” has ever made a “free” decision (What will you do to show this? Round up all the agents and prove their actions deterministic one-by-one?) Controlling the environment of a single agent and seeing if it is sufficiently predictable ignores the nature of the statement; no one thinks we have free will all the time, and many might even be skeptical that every agent has free will. This difficulty is inherent in the nature of questions that just require one example for them to be true. Most arguments against free will seem to take a strawman version of it that dodges the nature of the statement [8]. Dethroning free will seems even harder than determinism.

The conclusions I have here all stem from a certain stringiness about requirements. I think, after reading this, some people might accuse me of shifting the goal post too far. Couldn’t the actors in GoL reach a point where they were_reasonably confident_that their world was deterministic, even if they couldn’t predict the entire state of their game board? This was actually my original stance. Perhaps they could segment a portion of the board off for an experiment, or just predict the behavior of one sufficiently complex creature within GoL? Difficulties defining_reasonably confident_aside*, the problem is when you admit some unavoidable error in your predictions, or control for the environment in a contrived way, you open yourself up to either defeating the purpose of the question, or leaving too large a modicum of doubt [9].

Another way to think about the falsifiability problem here is to compare a deterministic worldview to other claims we say we have knowledge of. If I, for example, claim I have the ability to lift 5 pounds, I can demonstrate this and be correct over and over, save some remarkable circumstances. If you claim the universe is deterministic, you have to be able to show that it is deterministic for arbitrary points in time; a task that quickly becomes due to measurement problems, as we’ve talked about in the post. Even if the world was truly deterministic, it would be functionally indeterministic.

This doesn’t mean looking into the topic isn’t worthwhile. These are still fun questions to ask, especially for people who enjoy multidisciplinary research. I’ll leave you with a meme that summarizes why I like these kinds of topics.

Notes

[1] Einstein’s denial of the role of chance in physics is well known. One of his most famous statements was that “God does not play dice”. Einstein cared deeply about this issue, andabout the philosophy of science in general. Neils Bohr and Einstein disagreed about the nature of chance in quantum mechanics. This was one of the few times Einstein ended up being wrong about something.

[2] The observation of agravitational singularityare the particular circumstances. I try my best to do the Cosmic Censorship hypothesis justice here, but philosophically it strikes me as fishy. In it, Roger Penrose— who, by the way, is an excellent philosopher in his own accord— distinguishes between*naked_singularities (those that_can_be observed) and normal singularities (those past theevent horizonin a black hole, which_cannot_be observed). To Penrose, normal singularities do not break causation because they cannot be observed by the rest of the universe, but naked ones do. Where I’m at right now, it seems to me that if we want determinism to be truewe must hold that it is true under_all circumstances,_and not just all observable circumstances. It appears that, for Penrose, unobservable things don’t count here, even if they’re a necessary consequence laws dictating things we can observe. My hunch is that there’s something missing in my understanding of Penrose’s ontology. If anyone well-versed in cosmology comes bothers to read this, I’d love to have a chat.

[3] Attempts to argue otherwise are often referred to as “Hidden Variable Theory” after the unobserved variables these theories posit to exist. Albert Einstein was the first to advance such a theory in his — quickly withdrawn — paper titled*“Does Schrödinger’s wave mechanics determine the motion of a system completely or only in the statistical sense?”_

[4] In particular, I’m referring to the wave function collapse and quantum indeterminacy. It’s worth noting that while it is unclear why a small particle might appear in one place over another, many are skeptical that such phenomena scale to the “macro-level”.

[5] Indeterminism is distinct from free will because it only requires that_some_event can occur without a cause. Indeterminism makes no statement about whether people can make their own decisions, so it’s a necessary condition for free will, but not a sufficient one. I’ve tried to make this post strictly about determinism vs indeterminism, largely ignoring free will, but it’s worth noting that many people take randomness as being free will itself. Some argue that indeterminacy “bubbles up” from the quantum level to the macro level, and might even agree with the statement that a particle radioactive decay might be considered to have some sort of “will”. I won’t dive into theories like those here — they’re much more speculative than the one I’m putting forth here — but it’s worth noting that they exist. If you’re interested in other takes on how uncertainty relates to free will, I’d recommend a paper byScott Aaronsonwhere he argues that Knightian uncertaintymight provide some basis for free will. Werner Heisenberg also has aninteresting argument. Finally, no list of bizarre explanations for quantum indeterminism would be complete without the Von-Neumann-Wigner interpretation, where John Von-Neumann — arguably the smartest person in history— makes the case that consciousness is a necessary condition for quantum measurement.

[6] In fact, reconstructing history perfectly, even within GoL, is impossible, even with all of the rules of the game. GoL is irreversible. Two different states can lead to the same following state, and it is impossible to determine which one came first.

[7] This is often referred to as “agent-causal libertarianism”. To many, it’s a fairly unsatisfactory version of free will, but, to me, it’s one of the few iterations of free will that makes sense. For a complete discussion I’d recommend the Stanford philosophy entry here.

[8] Oftentimes these argumentswill attack the “popular notion of free will”. I can think of no better way to disguise attacking the weakest version of someone’s argument.

[9] Suppose we want to do an experiment on free will by putting someone in a box with no windows hidden far-far away from everyone else in the universe and predict how they will behave. Does this flavor of experiment really dismiss free will, or does it exclude free will from the experimental group by design? I also find it difficult to imagine that our actors would ever find that allowing for “almost perfect predictions” would be OK. Not just because of sensitivity to initial conditions causing far-out predictions to become impossible, but because what might seem like just experimental error often turns out to be the birth of a overturning of an existing theory. At a certain point, you have to take a leap of faith to believe in determinism, and even then, it’s functionally the same as indeterminism due to the margin of error in your measurements.